What are the most important IoT security best practices?

Effective IoT security in industrial systems requires hardware-rooted trust, not just software measures. The five non-negotiable practices are: 1) hardware root of trust (TPM or secure element) for identity and key storage, 2) authenticated secure boot chain from hardware to application, 3) encrypted communications with mutual TLS/DTLS, 4) signed, rollback-protected firmware updates (OTA), and 5) network segmentation isolating OT from IT. For hardware security design services, see our Embedded Security & IoT practice.

What Competitors Won’t Tell You About IoT Security

Most IoT security guides focus on IT security applied to IoT — firewalls, patching, access control, Zero Trust. These are necessary but insufficient for industrial systems.

Here’s what they miss:

| What competitors cover ❌ | What actually matters ✅ |

|---|---|

| “Change default passwords” | Hardware root of trust — passwords can be extracted from flash; secure elements cannot be read |

| ”Use encryption” | Key management lifecycle — where are keys generated, stored, rotated, and revoked? |

| ”Keep software updated” | Authenticated firmware updates — how do you prevent a malicious update from bricking 10,000 devices? |

| ”Segment your network” | Physical tamper protection — what happens when someone has physical access to the device? |

| ”Run antivirus” | There is no antivirus for embedded systems — security must be designed into the hardware |

| ”Monitor for anomalies” | A compromised device can lie — only hardware attestation proves device integrity |

This guide addresses IoT security from the hardware up — the perspective that matters when you’re designing products, not just deploying them.

The Real Cost of Getting It Wrong

Industrial IoT security failures aren’t abstract — they have quantifiable consequences:

| Incident | Impact | Root Cause |

|---|---|---|

| Triton/TRISIS (2017) | Attempted explosion at Saudi petrochemical plant | Malware targeting safety instrumented systems (SIS) |

| Colonial Pipeline (2021) | $4.4M ransom, US fuel supply disrupted for 6 days | Compromised VPN credential, no MFA on OT access |

| Verkada cameras (2021) | 150,000 cameras compromised (Tesla, hospitals, prisons) | Hardcoded admin credentials in firmware |

| Oldsmar water (2021) | Attempted poisoning of water supply (sodium hydroxide 100×) | Remote access to SCADA without authentication |

| MOVEit (2023) | 2,500+ organizations breached | Unpatched file transfer appliance |

Common thread: Every major IIoT breach exploited either missing hardware security, unpatched software, or inadequate access control. Software-only security failed in every case.

Average cost of an industrial security breach: €4.7 million (IBM Cost of a Data Breach 2025). For critical infrastructure, the cost can include human safety.

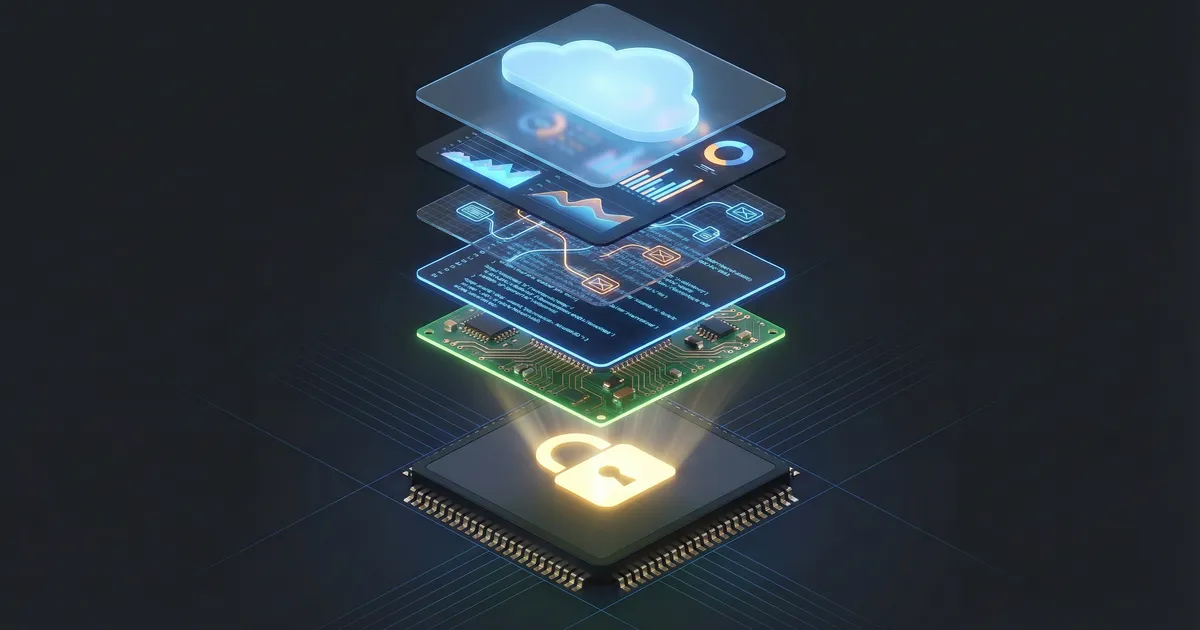

The Security Architecture Stack

Securing an industrial IoT device requires defense at every layer:

┌────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ CLOUD / BACKEND SECURITY │

│ API authentication, certificate management│

│ Device fleet management, audit logging │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ APPLICATION SECURITY │

│ Input validation, secure coding, SBOM │

│ Encrypted storage, access control │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ COMMUNICATION SECURITY │

│ Mutual TLS, DTLS, encrypted MQTT │

│ Certificate pinning, key rotation │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ FIRMWARE SECURITY │

│ Signed updates, rollback protection │

│ Secure bootloader, code signing │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ OS / RTOS SECURITY │

│ Memory protection, privilege separation │

│ Secure storage API, watchdog │

├────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│ ★ HARDWARE SECURITY (Foundation) ★ │

│ Secure element / TPM, secure boot ROM │

│ Hardware RNG, tamper detection, PUF │

│ Fused keys, debug port lockdown │

└────────────────────────────────────────────┘Key principle: Security flows upward. If the hardware layer is compromised, every layer above it is compromised. This is why hardware security is the foundation, not an afterthought.

Best Practice 1: Hardware Root of Trust

The most critical decision in IoT security design is establishing a hardware root of trust — an immutable, tamper-resistant component that serves as the security anchor for the entire system.

TPM vs Secure Element vs MCU-integrated: Which to Use?

| Feature | Discrete TPM | Secure Element | MCU-Integrated (TrustZone/PSA) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Standards | TCG TPM 2.0 (ISO 11889) | CC EAL5+/EAL6+ | PSA Certified (Level 1–3) |

| Key storage | RSA/ECC keys, sealed storage | ECC/AES keys, X.509 certs | Isolated secure enclave |

| Tamper resistance | Medium (discrete chip) | High (designed for physical attacks) | Low–Medium (shared die) |

| Cost | €2–€8 per unit | €0.50–€3 per unit | €0 (built into MCU) |

| Crypto performance | Moderate (I2C/SPI bus bottleneck) | Moderate | Fast (on-die) |

| Best for | PC/server-class devices, Linux systems | IoT devices, smart cards, constrained | Cost-sensitive MCU designs |

| Example chips | Infineon SLB 9670, Microchip ATECC608B | NXP SE050, Infineon OPTIGA Trust M | STM32U5 (TrustZone), nRF5340 |

When to Use Which

- Battery-powered IoT sensor → MCU-integrated TrustZone (lowest cost, acceptable for PSA Level 2)

- Industrial gateway → Discrete TPM 2.0 (TCG standard, auditable, Linux support)

- Payment terminal or critical infrastructure → Secure Element (CC EAL5+, highest tamper resistance)

- FPGA-based system → FPGA bitstream encryption + external secure element for key storage

Implementation Checklist

□ Unique device identity (X.509 certificate per device, not per batch)

□ Private key generated on-chip (never leaves the secure element)

□ Hardware RNG for key generation (not software PRNG)

□ Monotonic counter for rollback protection

□ Debug port (JTAG/SWD) disabled in production firmware

□ Fuse bits set to prevent flash readout

□ Tamper detection GPIO (optional, for high-security applications)For detailed implementation patterns, see our Embedded Security & IoT service page.

Best Practice 2: Secure Boot Chain

A secure boot chain ensures that only authenticated, untampered code runs on the device, from power-on to application:

Power On

↓

1. Boot ROM (immutable, in silicon)

→ Verifies bootloader signature using OTP fused public key

↓

2. Bootloader (first updatable stage)

→ Verifies firmware image signature (ECDSA P-256 or Ed25519)

→ Checks rollback counter (prevents downgrade attacks)

↓

3. Firmware / RTOS

→ Verifies application integrity

→ Initializes secure storage

↓

4. Application

→ Establishes TLS connection to backend

→ Normal operation beginsCommon Secure Boot Mistakes

| Mistake | Consequence | Fix |

|---|---|---|

| Storing signing key alongside firmware | Attacker extracts key, signs malicious firmware | Key in secure element only, never in flash |

| No rollback protection | Attacker flashes old vulnerable firmware | Monotonic counter in OTP fuses |

| Verifying only the first stage | Later stages can be modified undetected | Chain of trust — each stage verifies the next |

| Debug port left open in production | JTAG/SWD bypasses entire boot chain | Fuse JTAG disable before deployment |

| Using SHA-256 only (no signature) | Hash can be recalculated for modified firmware | Use ECDSA or Ed25519 signature verification |

FPGA-Specific Secure Boot

FPGAs have unique secure boot requirements because the entire hardware configuration is loaded at power-on:

- Bitstream encryption — AES-256 encryption of the FPGA configuration file

- Bitstream authentication — RSA/ECDSA signature verification before loading

- Key storage — eFUSE or battery-backed RAM for encryption keys

- Fallback — golden/recovery bitstream if primary authentication fails

- Partial reconfiguration — update only portions of the FPGA without reloading everything

AMD/Xilinx and Intel/Altera FPGAs both support these features natively. Our FPGA Design Services include security architecture from the beginning of every project.

Best Practice 3: Encrypted Communications

Every data path in an IoT system must be encrypted and authenticated:

Protocol Selection for Industrial IoT

| Protocol | Security | Overhead | Best For | Recommendation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MQTT + TLS 1.3 | Strong | Medium (TCP + TLS) | Cloud-connected devices, telemetry | ✅ Default choice for IP-capable devices |

| MQTT-SN + DTLS | Strong | Lower (UDP-based) | Constrained devices, lossy networks | ✅ Good for LoRaWAN/NB-IoT |

| CoAP + DTLS | Strong | Low | RESTful constrained devices | ✅ Alternative to MQTT for request/response |

| OPC UA | Strong (built-in) | High | Industrial automation, SCADA | ✅ Standard for factory floor |

| Modbus TCP | ❌ None natively | Low | Legacy industrial | ⚠️ Wrap in VPN or TLS tunnel |

| BLE | Medium (AES-CCM) | Low | Short-range sensors | ⚠️ Adequate for non-critical data |

| LoRaWAN | AES-128 (built-in) | Very low | LPWAN sensors | ✅ Acceptable for sensor data |

Mutual TLS: Why Server-Only TLS Is Not Enough

Standard HTTPS/TLS authenticates only the server. In IoT, the device must also authenticate to the server (mutual TLS / mTLS):

Standard TLS:

Device → "I trust you, server" (verifies server certificate)

Server → "I don't know who you are" (accepts any client)

Mutual TLS:

Device → "I trust you, server" (verifies server certificate)

Server → "Prove you're a real device" (verifies device certificate)

Device → Presents X.509 certificate from secure element

Server → Verified — connection establishedWhy mTLS matters: Without device authentication, an attacker can impersonate a device, inject false sensor data, or exfiltrate commands intended for legitimate devices.

Key Rotation and Certificate Lifecycle

Manufacturing → Device provisioned with initial certificate

↓

Deployment → Certificate registered with IoT platform

↓

Operation → Certificates rotated every 1-2 years

↓

Decommission → Certificate revoked, device wipedKeys should never be shared across devices. Each device gets a unique keypair generated in its secure element during manufacturing.

Best Practice 4: Secure Firmware Updates (OTA)

The ability to update deployed devices is both a security requirement and a security risk. A compromised update mechanism gives attackers root access to your entire fleet.

OTA Update Security Requirements

| Requirement | Purpose | Implementation |

|---|---|---|

| Code signing | Verify update authenticity | ECDSA-P256 or Ed25519 signature |

| Encryption | Prevent reverse engineering of firmware | AES-256 encryption of update package |

| Rollback protection | Prevent downgrade to vulnerable version | Monotonic counter in OTP/secure element |

| Atomic update | Prevent bricking from interrupted update | A/B partition scheme or delta updates |

| Version verification | Ensure correct firmware for correct device | Hardware ID + version check before apply |

| Audit trail | Track update status across fleet | Backend logging of per-device update status |

A/B Update Architecture

Flash Layout:

┌────────────────┐

│ Bootloader │ Verifies active partition

├────────────────┤

│ Partition A │ ← Currently running (v2.1)

├────────────────┤

│ Partition B │ ← New update written here (v2.2)

├────────────────┤

│ Secure Store │ Keys, certificates, config

└────────────────┘

Update Process:

1. Download v2.2 to Partition B (while v2.1 runs)

2. Verify signature of v2.2

3. Check rollback counter (v2.2 > v2.1 ✓)

4. Mark Partition B as "pending"

5. Reboot → bootloader tries Partition B

6. If boot succeeds → mark B as "active"

7. If boot fails → rollback to Partition A automaticallyThis is not optional — the EU Cyber Resilience Act mandates authenticated firmware updates for all connected products sold in the EU from 2027. See our CRA Compliance Checklist.

Best Practice 5: Network Segmentation and Zero Trust

The Purdue Model for Industrial Networks

Industrial networks should follow layered segmentation:

Level 5: Enterprise │ ERP, email, internet

───── DMZ ─────────────┤ Firewall + IDS

Level 4: Business │ MES, historian, reporting

───── DMZ ─────────────┤ Industrial firewall

Level 3: Operations │ HMI, SCADA, engineering

────────────────────────┤ Managed switch + ACL

Level 2: Control │ PLCs, DCS, RTUs

────────────────────────┤ Physical isolation

Level 1: Field │ Sensors, actuators, drives

Level 0: Process │ Physical equipmentZero Trust for OT — Practical Implementation

Zero Trust in industrial environments doesn’t mean “authenticate everything with MFA” — some devices don’t even have a screen. Practical Zero Trust for OT means:

- Network micro-segmentation — each device or device group in its own VLAN

- Device identity — X.509 certificate-based authentication (not passwords)

- Least privilege — devices can only communicate with their controller, not with each other

- Encrypted east-west traffic — inter-device communication encrypted even inside the OT network

- Continuous monitoring — anomaly detection on traffic patterns (not payload inspection, which breaks real-time)

- No implicit trust — a device authenticated 5 minutes ago must re-authenticate if its behavior changes

Best Practice 6: Physical Security (The Forgotten Layer)

Most IoT security guides stop at the network. But industrial devices are deployed in physically accessible locations — factory floors, utility cabinets, outdoor installations.

Physical Attack Surface

| Attack Vector | Risk | Mitigation |

|---|---|---|

| Debug ports (JTAG/SWD) | Full firmware extraction, key dump | Fuse disable, cover with epoxy in production |

| Flash readout | Firmware reverse engineering | Flash read protection bits + encrypted firmware |

| Bus sniffing (I2C/SPI to secure element) | Key extraction during operation | Use encrypted bus communication or on-die integration |

| Side-channel (power analysis, EM emanation) | Key extraction from crypto operations | Constant-time crypto, hardware countermeasures |

| Fault injection (voltage glitching, laser) | Bypass secure boot, skip authentication | Redundant checks, glitch detectors, secure elements with FI protection |

| Device replacement | Substitute compromised device | Device attestation + fleet management |

PCB-Level Security Measures

For high-security industrial designs, consider:

- Tamper-evident enclosures — physical seals that show if device was opened

- Tamper-responsive — active mesh over sensitive components, wipes keys on breach

- Conformal coating — protects PCB traces from probing

- BGA packages — ball grid array components are harder to probe than QFP

- Potting compound — encapsulate security-critical components in epoxy

EU Regulatory Compliance

EU Cyber Resilience Act (CRA) — Hardware Requirements

The CRA (effective 2027) imposes specific obligations on hardware manufacturers:

| CRA Requirement | Hardware Implementation |

|---|---|

| Security by design | Hardware root of trust, secure boot from ROM |

| Vulnerability handling | OTA update capability, PSIRT process |

| SBOM (Software Bill of Materials) | Include firmware components, bootloader version, crypto libraries |

| No known exploitable vulnerabilities at release | Pre-release security testing, penetration testing |

| Authenticated updates throughout lifecycle | Signed OTA, rollback protection, A/B partitioning |

| Report actively exploited vulnerabilities within 24h | Incident response plan, fleet monitoring |

IEC 62443 — Industrial Automation Security

The international standard for industrial cybersecurity defines Security Levels (SL):

| Level | Meaning | Hardware Requirements |

|---|---|---|

| SL 1 | Protection against casual violation | Password protection, basic access control |

| SL 2 | Protection against intentional violation with low resources | Unique identity, signed firmware, TLS |

| SL 3 | Protection against sophisticated attack with moderate resources | Hardware root of trust, tamper detection, mTLS |

| SL 4 | Protection against state-level attack with extended resources | Secure element (EAL5+), active tamper response, formal verification |

For projects targeting IEC 62443 SL 3+, hardware security design must be incorporated from the architecture phase. See our EU Compliance Guide.

ETSI EN 303 645 — Consumer IoT Security

The European baseline standard for consumer IoT mandates:

- No universal default passwords

- Implement means to manage vulnerability reports

- Keep software updated

- Securely store sensitive security parameters

- Communicate securely

- Minimize exposed attack surfaces

Security Verification and Testing

Pre-Production Security Testing Checklist

□ Penetration testing (firmware extraction, debug port access)

□ Fuzzing (protocol parsers, firmware update handler)

□ Side-channel analysis (if handling high-value keys)

□ Secure boot bypass testing (glitching, fault injection)

□ Certificate validation testing (expired, revoked, wrong CA)

□ OTA update testing (rollback, interrupted, corrupted)

□ Radio security testing (if wireless: BLE, Wi-Fi, LoRaWAN)

□ Physical access testing (JTAG, flash readout, bus sniffing)

□ Compliance verification (CRA, IEC 62443, ETSI EN 303 645)Tools for Embedded Security Testing

| Tool | Purpose | Cost |

|---|---|---|

| Ghidra | Firmware reverse engineering | Free (NSA open-source) |

| Binwalk | Firmware extraction and analysis | Free |

| ChipWhisperer | Side-channel analysis and glitching | €300–€3,000 |

| Logic analyzer (Saleae) | Bus protocol sniffing | €150–€1,500 |

| JTAG debugger (J-Link) | Debug port access testing | €50–€1,000 |

| AFL/LibFuzzer | Protocol fuzzing | Free |

| OpenSSL s_client | TLS configuration testing | Free |

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the biggest IoT security risk?

The biggest risk is no hardware root of trust. Without it, firmware can be extracted and cloned, encryption keys can be read from flash memory, and secure boot can be bypassed. Software-only security can always be defeated with physical access to the device. A €1 secure element eliminates the most impactful class of attacks.

How much does IoT security add to product cost?

A basic security stack (secure element + secure boot + encrypted OTA) adds €1–€5 per unit in component cost and €10,000–€30,000 in development time. Compare this to the average industrial breach cost of €4.7 million. IoT security is not a cost center — it’s risk mitigation with quantifiable ROI.

Can existing IoT devices be secured retroactively?

Partially. You can add network-level protections (segmentation, monitoring, VPN) to deployed devices. But device-level security (secure boot, hardware root of trust) cannot be added after manufacturing — it must be designed in. This is why security architecture decisions must be made at the beginning of the V-Model development process, not at the end.

What is the difference between IT security and OT security?

IT security prioritizes confidentiality (protecting data). OT security prioritizes availability and safety (keeping systems running and people safe). In OT, a security patch that causes 5 minutes of unplanned downtime may cost more than the vulnerability it fixes. This is why OT security requires careful change management, tested patches, and often hardware-level solutions that don’t require reboots.

How does IEC 62443 differ from the EU CRA?

IEC 62443 is a voluntary international standard for industrial automation security, widely adopted in manufacturing. The EU CRA is a mandatory regulation for all products with digital elements sold in the EU. They are complementary: IEC 62443 provides detailed technical implementation guidance; the CRA provides the legal obligation to implement security. Products certified to IEC 62443 SL 2+ will likely meet most CRA requirements.

Do FPGAs need different security than MCUs?

Yes. FPGAs have unique attack surfaces because the entire hardware configuration (bitstream) is loaded at power-on. Key differences: 1) bitstream must be encrypted (AES-256) and authenticated (RSA/ECDSA), 2) configuration keys stored in eFUSE or battery-backed RAM, 3) partial reconfiguration must also be authenticated, and 4) FPGA fabric itself can implement security functions (hardware crypto, PUF) that MCUs cannot. See our FPGA security design services.

How Inovasense Secures Industrial IoT

Security is built into every project we deliver, not bolted on:

- Security architecture — threat modeling, secure element selection, key management design

- Secure boot implementation — from boot ROM through application on ARM, RISC-V, and FPGA platforms

- Firmware security — signed OTA updates, A/B partitioning, rollback protection

- Hardware design — tamper-resistant PCB layouts, debug port protection, conformal coating

- FPGA security — bitstream encryption, hardware crypto engines, PUF integration

- Compliance — CRA readiness, IEC 62443, CE marking

- Testing — penetration testing, side-channel analysis, security audit

Contact us to discuss your IoT security requirements — whether for a new product design or hardening an existing one.